In the latest Inside Higher Ed 2019 Survey of College and University Presidents it was no surprise to see that the majority of presidents are confident that their institutions will be financially stable over the next five years.

What I was quite surprised to read was that 14% of college presidents say they could see their own college closing or merging in the next five years. Although 14% seems small, over a few thousand institutions that’s a good couple of hundred colleges. Normally it’s external analysts prophesying the demise of colleges but this time it’s the actual people in charge forecasting their own demise.

An even scarier number was that 96% of president’s anticipate at least some closures this year. So it seems like colleges closing or merging are becoming more of the norm, funnily enough though, the heading for the article is “The Mood Brightens”. I suppose if you are not in fear of closing then things are looking up, as one commenter stated on the website “but I would say that an expectation that 13% of PUBLIC colleges merging or closing in the next 5 years would only brighten the mood of the other 87%”

To dig into the survey a bit more, as mentioned in the comment above, this 14% on average is broken into 13% for Public and 15% for Private Nonprofit institutions. The public number surprised me quite a bit as well because the majority of the articles I’ve read seem to focus on small private colleges or for-profit colleges that are closing or have closed.

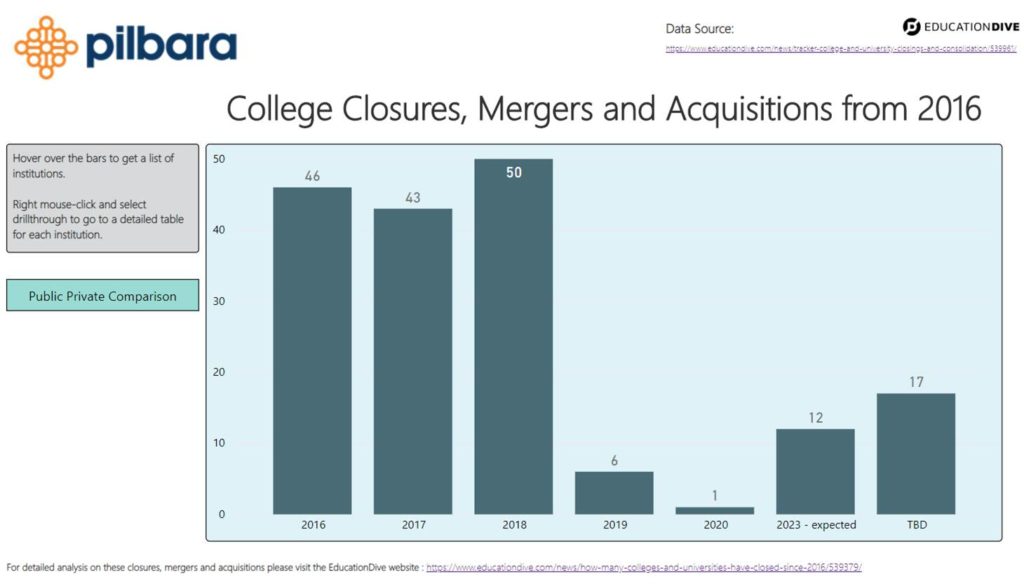

So this got me thinking about what has been the closure/merger rate over the last few years and luckily the folk over at EducationDive have done the analysis on data back to 2016:

Digging into their numbers there have been a staggering 139 institutions that have closed, merged or consolidated since 2016 with a further 36 planned to close or merge from 2019 to 2023. The majority of these are Private for-profit institutions (74) and the remainder are Private Nonprofit (63) and Public (36).

Looking at the public numbers since 2016 there have been 12 institutions that have merged already with the other 24 expected to merge or consolidate some time in the near future.

To make it a bit easier to visualize I’ve taken the EducationDive data and thrown it into Power BI. I’ve included some screenshots in this post but you can see the live reports here. There is also a pie chart showing the breakdown of Public vs Private institutions if you click on the “Public Private Comparison” button in the live report.

Now going back to the President’s survey, the key point here is “In the next five years” that’s important because that buys the institution time to do something about it now.

Do you fear your institution could close or merge in the next five years? If so, please let me know in the comments below about what your institution is planning on doing to address this concern.

So what can an Institution do?

Fundamentally there are two primary options – cut cost or increase revenue. A lot of articles written about institutions in trouble seem to be focused primarily on increasing revenue including increasing tuition, alumni donations, out of state or international students.

A lot of these articles also state that the institution has been through a cost cutting exercise already and they have “cut to the bone”. However, I like a quote from Mitch Daniels – President of Purdue University discussing cost cutting at his institution “… he said much of the trimming has been hidden from view. Daniels used a butcher’s metaphor, noting, “The fat is marbled through the animal — you look in vain for too many great big strokes. There may be a few — the health-care plan was one — but mainly it’s the accumulation of small economies…”

So there are the “big pieces of fat” that are easy to find and cut but there are a number of other costs that a relatively hidden from view and these need to be examined. So cutting costs is not so much about using a meat cleaver but rather a surgical scalpel.

So do you focus on cost or revenue? In the words of that great taco shell commercial “Why not do both?” Focusing on cost and revenue brings us to the wonderful metric of margins, the difference between the full cost of delivering a course or a research project and the revenue received for them.

Knowing your detailed margins is fundamentally important for developing strategies to survive any impending closure due to financial problems.

Why is that? A not-for-profit institution, as the name implies, is not driven by a profit goal but rather driven by a core mission. As Matt Easdown once said, while he was Deputy CFO at the University of Sydney, “Universities are not-for-profit, but very much not-for-loss either.”

Financial sustainability requires the institution to understand their detailed margins so that they can make mission based decisions and understand that if that generates a financial loss somewhere, then it can be covered by another area of the institution.

Cross-subsidization is very common in not-for-profit institutions, unfortunately making this cross-subsidization visible and using it to the institutions advantage is not so common.

Let’s take a look at some real examples, these are not institutions that fear closing or merging, but they both had financial issues they needed to deal with.

Embry-Riddle: Taking a Campus from a $3m loss to $14m positive margin

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University used detailed modelling to turn a campus’ financial performance around. Adam Raab explained at the Academic Impressions conference last December that one of their campuses had poor financial performance. Their first thought was to cut programs to cut costs. Unfortunately that would also cut revenue and if any tenured staff were involved in these programs then they still need to be paid anyway, so it might not remove that much cost.

So they looked for a better option, which was to grow, but they didn’t have the data to support this decision. The first thing they did was to build a very quick and simple Activity-Based Cost (ABC) model to provide the data required. The objective was to find out which programs are working and which ones aren’t, i.e. those with positive margins and those with negative margins.

This turned out to be very successful and the campus has significantly improved going from a $3 million loss to a $14 million positive margin. Their model has improved quite a lot over a ten year period and is still used extensively today.

NYIT: Double whammy- declining enrollments and margins

Mark Hampton, formerly with NYIT and now with Washington College explained how NYIT actually used their ABC model.

The primary reason for the implementation of the model was that NYIT had the double whammy of declining enrollments and declining margins. Prior to implementing ABC, NYIT had a direct cost model that didn’t distinguish between programs and activities. It neglected indirect costs (which were substantial) and while their initial model was useful it didn’t lead to actionable strategies.

After the ABC model was implemented they had a huge amount of data that allowed analysis of School and Department margins, Faculty effort and research, and margins of Course and Course Instance (when, where and how taught) and Degree and other teaching programs.

Some real questions that the model was successfully used to answer included “To what extent do we subsidize our global activities?”, “Which Programs should we grow and which should we consider phasing out?”, “What additional overhead does having two flagship campuses add?”

One very interesting insight from their analysis was the incorrect assumption that teaching a course in two sites using distance-learning (DL) technologies was an effective way to address instructional costs.

The ABC model showed that additional costs associated with DL courses made it very difficult for these courses to break even, given the institutions limits on the numbers of students in the remote site and the need for proctoring at that site. DL courses tended to mask very small sections: 4 students locally plus 4 students in the remote site still amounts to a small course.

Areas of Analysis

So in summary there are a number of things institutions can do to help address a pending financial crisis including, but not limited to:

- Growing programs rather than cutting programs and only cut those programs where the financial performance will be better and not worse.

- Improving the performance of under performing programs.

- Optimizing the delivery of courses.

- Ensure cross-subsidization is visible so that mission based decisions can be made and the financial impact can be calculated and mitigated.

But the very first thing you need is a thorough understand of your underlying economics, the way your institution currently operates. Once this is visible then use this data to your advantage and look for opportunities to survive!