Universities are constantly jugging resources – research brings the rankings and brand while teaching brings the bulk of the revenue. In Australia, this has become even harder in 2018 with the capping of CGS (Commonwealth Grant Scheme) funding.

Universities see their students as customers and provide a range of services, both inside and outside of the lecture theatre, to entice, retain, assist and support them throughout the students’ university life. This often includes providing a range of options regarding when, where and how a course (subject) is offered.

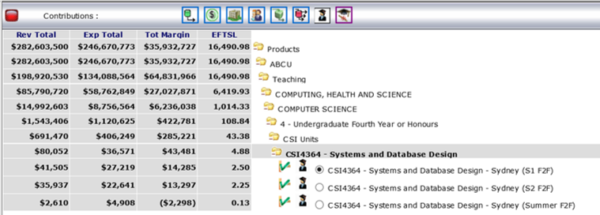

Having a cost model that provides you with the margin associated with a course name, whilst being suitable for many things, won’t help you make decisions regarding the when, where and how. As shown below, CSI4364 is making a healthy margin….but it isn’t telling you the whole story.

To do this, each course needs to be broken down by the three components making up the when, where and how:

- When: teaching period / semester / term

- Where: campus / location

- How: face to face / online / blended / external

It is not until you can pull apart the cost of delivering a course to this extent that the range of decision options become visible.

As can be seen above, whilst the course overall is doing well, it is being taught in three separate instances. In this case, they are all in Sydney, all face to face, but being taught in three different sessions – semester 1, semester 2 and summer. The two primary sessions have around 20 students enrolled in each instance and are showing a positive margin. However the course instance being taught over the summer period only has one student (0.125 EFTSL) enrolled with the result being that the summer version of this course is making a loss.

So now the cost model is providing you with additional information that can assist in some more complex decision making.

Is there a specific reason why the course needs to be taught in summer school?

- If there is, is there a way to increase enrolments in the course? Note that cannibalising students from the primary sessions isn’t necessarily the answer here. But increasing overall enrolments with specific attention paid to the summer session could be an option.

But if there is no specific reason, then the next phase of the analysis should be looked at. Assuming that next summer the enrolments were the same, would the university save the $2,300 that it lost on teaching this course during summer if it was cancelled? It depends on what happens to that one student…

Option A – the student enrols in either the semester 1 or 2 course instance instead.

- The university retains the direct income related to the student.

- The fixed costs associated with teaching that course over summer aren’t saved (things like the provision of HR and IT etc). Instead (assuming everything else remains constant at the university), the portion of fixed costs will be reallocated out over all the other courses being taught.

- The asset space costs associated with the rooms that were booked to deliver that course will go into the ‘unused space’ pool and be redistributed back out over the courses being taught (depending on the excess capacity rules used within your cost model).

- A portion of the direct costs associated with teaching that course over summer could be saved, for example, if casual staff had been employed to teach it.

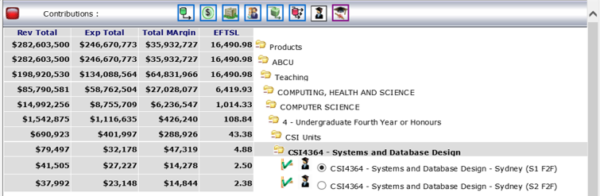

By running this scenario through the model, we can see that the margin for the course has gone from $43,481 to 47,319 – just over $3,800 more.

Option B – the student doesn’t enroll at all.

- The university loses the direct income related to the student.

- All the fixed costs remain.

- Some of the direct teaching costs are saved.

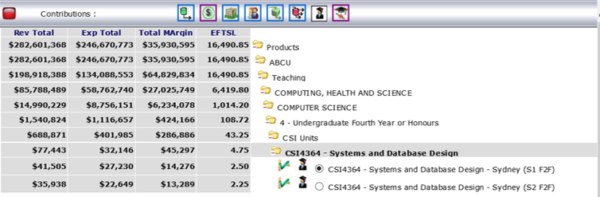

This results in an overall margin improvement of around $1,800 for the course, but the university’s margin has reduced by $2,132 – a worse outcome for the university overall.

Cost of Online Delivery versus Face-to-Face Delivery

The need to understand the cost and quality benefits associated with different delivery modes is increasing. Online teaching is not new. However, is the time saved by not running lectures and tutorials outweighed by the potential need to spend more time per student?

The only way to quantify any cost savings (or increases) directly related to online teaching is to firstly have a very good understanding of the cost of delivery face-to-face and what the course profiles are relating to assessment and student contact.

This is further complicated by additional factors that can blur the potential cost savings related to online delivery, for example:

- Blended delivery, where the lectures may be delivered online and the students turn up just for tutorials or labs;

- Online training being delivered by an external provider, often for a percentage share of the revenue earned via the student; and

- Having an external partner that may recruit and manage the online students, but not teach them, again for either a revenue percentage, or possibly a direct fee per student.

A Pilbara Group predictive model allows you to create alternative ‘delivery method’ scenarios, which together with other variables, such as class size, allows the user to model these types of changes quite easily.