The Coronavirus is creating headlines around the world and here in Australia it’s having an impact on some universities who are delaying the start of the school year or starting the school year online initially. There might also be a financial impact but hopefully not a permanent one, but what if there was a permanent impact? Many Australian and North American universities have a significant proportion of their student population as international students. If there is a sudden and permanent decline in this student population, what impact would that have on the institution?

This is one type of scenario we explored as part of the LH Martin Institute Leading Universities Program. This program was established to teach senior university executives how to manage a university. These types of financial stress tests provide valuable insight into the resilience of the institution. Like the Coronavirus epidemic there are many types of “stresses” that can be imposed with little warning on universities and colleges. These can come in various forms but likely ones are changes to Government policy or international disputes which are completely out of the control of universities but can still have a significant financial impact on the institution.

It’s worthwhile exploring some major stress scenarios to see what the overall financial impact would be and then have some contingency plans in place.

The Predictive Model

Our predictive model is a financial model designed to take resource consumption trends of previous years and forecast one to ten years into the future based on changing a range of variables. A major benefit of the predictive model is that multiple scenarios can be developed covering a wide range of possible “what ifs” and then quickly and easily compared to determine the optimum way forward. This can be business as usual with simple changes to student numbers, adding removing programs/courses, changes to enterprise bargaining agreements etc. Or it can be used to forecast major disasters / threats to the institution or indeed a combination of both.

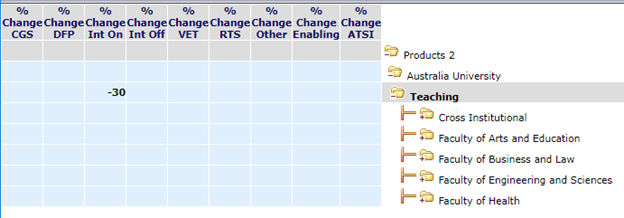

Let’s look at an example. What would happen if there was a permanent 30% decrease in the number of on-shore international students? It’s relatively simple to calculate the revenue impact and therefore the overall financial impact on the university as a whole. But what impact does it have down at the school, program and course level? – That is where it becomes much more complex.

Predictive Model Methodology

The predictive model starts calculating from the output of the institution, so in this case the student numbers, different types of students (Domestic, International onshore, International offshore etc.) and what they are enrolled in. It will then work out the teaching load required for all the individual programs/courses, in this case specifically the change in teaching load due to a drop in International Students.

So let’s run this scenario through our predictive model and see what it looks like and we’ll just focus on the high level impact to make it simple for this article, in the model we can go all the way down to individual course instance if desired e.g. Accounting 101, Semester 2, Campus A, Classroom (when, where and how taught).

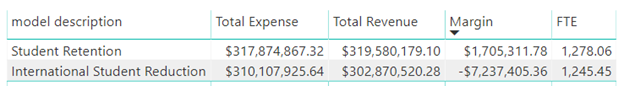

The table below shows the full university Expenses, Revenue, Margin and Academic and General Staff FTE. We are using our Student Retention demo model as the baseline model. In this case the Student Retention baseline model is showing a small positive Margin of $1.7 million. After applying a 30% reduction in International Onshore students the model calculates a $7 million negative margin.

However, as mentioned above, the predictive model will calculate the teaching load required for the reduced number of students, which would lead to a drop in the number of academic staff to teach and a drop in the number of general staff to support this reduced number of academic staff. But that’s not reality – a university probably wouldn’t just remove 33 staff overnight, so let’s re-run the model but try to keep the number of FTE the same.

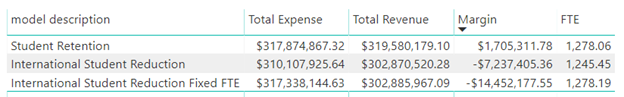

As we can see in the table below, the FTE numbers are pretty much the same between the top scenario and the bottom scenario (1,278) and as expected the negative margin is much greater because the expenses are back to the same level as the baseline scenario but the revenue has decreased.

In this example we’re just looking at one year. The next step would be to forecast 5-10 years into the future to see what the longer term financial impact would be and then run a range of different contingency scenarios to see which one would work best for the institution.

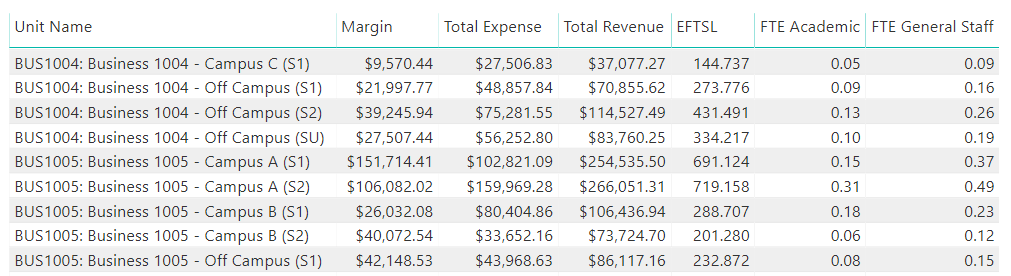

As mentioned before one of the major benefits of these types of Predictive Models is that it can calculate the financial impact all the way down to individual courses, as shown below. So these contingency plans can be developed based on a huge amount of detailed data and also with the active participation of individual schools.

The model is particularly useful for determining the impact of known issues as well, as an example, in Australia some states have changed the starting age for schools, this meant there was a reduced number of students working their way through primary school and high school before they start university. This is known as the “half cohort” and universities had many years to prepare for the half cohort. The model can be used to forecast the financial impact as it hits the university and works its way through the three to four year degree time frame. This way they can determine appropriate staffing levels and if there is a requirement to reduce staff numbers then this can be done via normal attrition through resignations and retirements rather than mass sackings during a financial crisis!

While this article has focused on modelling a particular crisis, such a model can be used in more traditional scenarios such as supporting the standard budgeting and planning process https://www.pilbaragroup.com/higher-education-shared-governance-requirements-10-11-budget-process-improvement-and-scenario-planning/