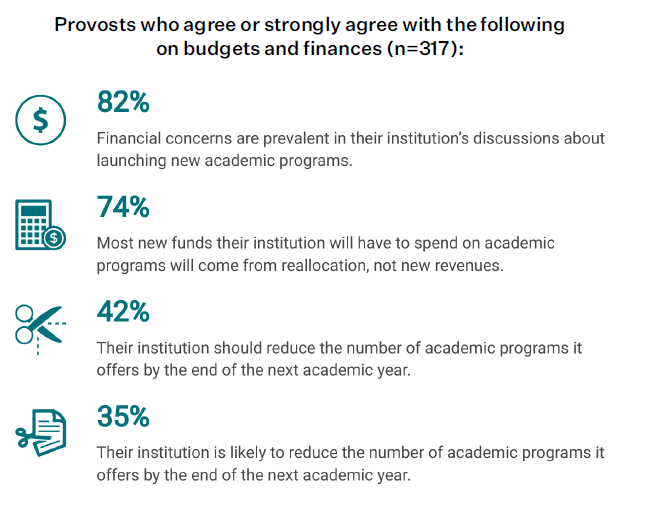

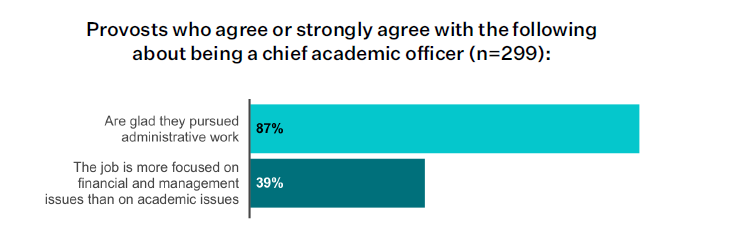

- The last 10-15 years of low interest and low inflation were great but are now gone.

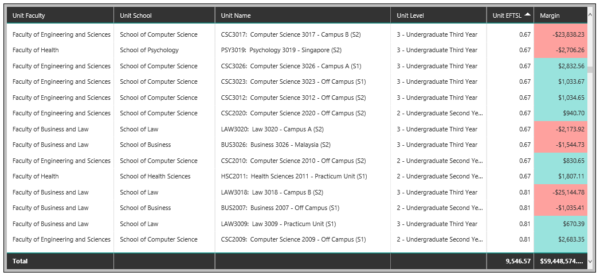

- You need the financial performance of every academic program and course available for review at any time.

- Comprehensive financial reviews of academic programs can no longer be done every 3-5 years, they need to be done at least annually.

- In this new economic reality the status-quo is no longer enough.

- The two must-have reports are Academic Program Financial Review – Deep Dive and Course Quadrant Analysis.

Traditional reviews look at a program’s curricular structure, the institution’s capacity (in terms of faculty, library resources, infrastructure, etc.) to deliver high-quality education in the area, student demand, and in some cases, the delivered quality of teaching. Typically, these types of reviews have not examined a program’s operational detail or economic factors like revenue, cost, and margin, despite the fact that these are important aspects of performance. These types of reviews could typically occur every 3-5 years. Things are changing so much nowadays that this timeframe is no longer viable for detailed financial analysis. But with the Pilbara Insights model this type of detailed financial analysis can be undertaken every year and for every Academic Program! Some of our universities are even considering every semester.

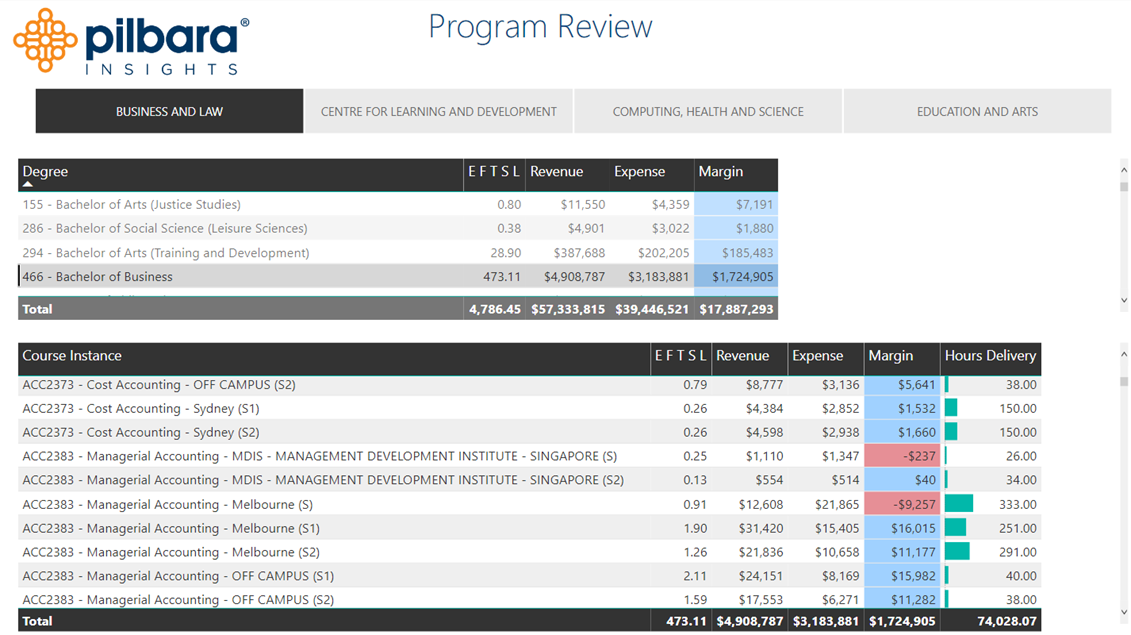

Step 1 is to examine the connections between a program and the courses that underpin it. This can be achieved with a simple dashboard that defines the linkages between courses and programs. Users can click on a course and see the program(s) that the students undertaking that course are registered against, and, more importantly, the revenue, expense and margin of both the course and the overall program(s) as well.

So, what can program reviewers do with this new information? For one thing, they can see yearly and trend data on every program’s cost, revenue, and margin, both in total and on a per-credit hour basis (or per EFTSL in Australia). Programs, not courses, represent the university’s face to the market. Without the explicit course-to-program linkages described above, there is a disconnect between data for the “production” side of the institution and data about the marketplace. Cross-referencing the two kinds of data should be a major objective in program review.

The linkages also permit reviewers to analyze the operational and economic detail available at the course level. For example, which courses are the most expensive, and which have the highest or lowest margins? What are the class sizes and teacher profiles, and what delivery methods are used? All this is based on the courses actually taken by students in each program, not on catalogue descriptions that include less-than-precise roadmaps about requirements and electives. For example, by looking at how the curriculum works in practice one can see where particular courses (including electives as well as requirements) and costs that may be disproportionately to their value for the particular degree being studied.

Finally, one can begin to identify courses that present bottlenecks to students’ progress toward their degrees. For example, looking at so-called WFD (withdrawal or a grade of F or D) can signal problems that reviewers might want to look into. The same is true for data on which courses are oversubscribed in particular semesters and locations. The model can easily include such variables if the institution’s data system records them, and thinking about benefits such as the above can provide the motivation needed to maintain the records.

Course Quadrant Analysis

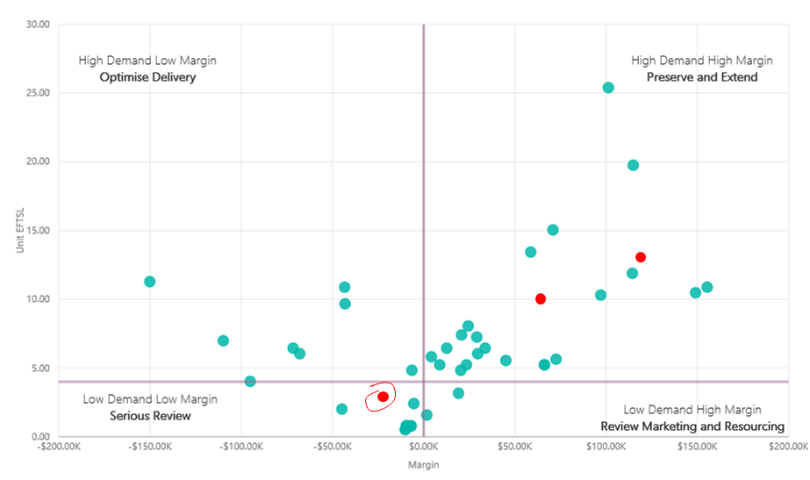

This report is used to highlight the financial performance of individual courses but also provides guidance on practical steps that can be taken to improve overall financial performance of the institution. By plotting student numbers against margin, it provides four distinct quadrants with respective actions that can be taken:

High Demand – Low Margin – Optimize the teaching delivery

High Demand – High Margin – Preserve and extend

Low Demand – High Margin – Review marketing and resourcing

Low Demand – Low Margin – Serious Review

The following is another extract from the same whitepaper co-written with Professor Bill Massy.

It is not uncommon for schools to receive pressure to address their low enrolment courses (subjects). For example, they may be told that they shouldn’t be running courses with fewer than, say, six students in them.

So how do you go about distinguishing the ‘good’ courses from the ‘bad’ courses? It is not a simple process, nor is it overtly obvious – course analysis is like peeling an onion, there are many layers that need to be looked at before getting to the core of the issue.

Identifying the courses to review:

While low enrollment courses are the frequent recipients of these types of reviews, they are not always the courses that should actually be addressed. Examining the scatter plot below (enrollment is plotted against the vertical and courses left of this axis are making a loss) we can see that some of the large losses are actually achieved by some of the courses with the highest enrollment. Reviewing the teaching methodologies for just a couple of these courses could have a much larger financial impact than all the low enrollment courses combined.

The course is an integral part of a program:

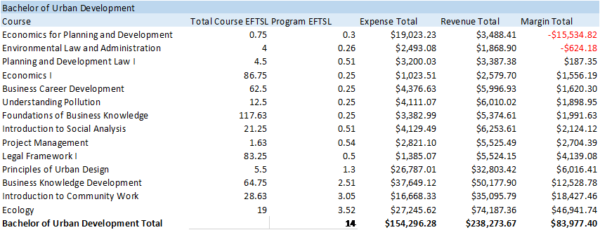

Low enrollment courses are frequently highly specialized third-year or fourth-year courses that form a key component of a program, so it does not pay to review any course in isolation. For example, a course may be highlighted as being low enrollment and making a loss:

But when put in perspective against the program it is supporting, the program as a whole looks very healthy (note that this program is only receiving 40% (or 0.3 out of 0.75 EFTSL[1] / enrolments) of the course):

[1] EFTSL – Equivalent Full-Time Student Load

So while an individual course may come under scrutiny it is essential to understand its role in the programs being offered, and what the health of the programs are in their entirety.

Are the low enrolment courses actually making a loss?

Just because a course has low student numbers it doesn’t necessarily mean it is running at a loss as shown in the table below. The delivery methods being used can have a high impact on the cost base of these courses. The types of students enrolled will also have a direct impact on the revenue, i.e. domestic vs international students. Courses with low student numbers can be profitable, so it doesn’t pay to just draw a line in the sand and blindly assume that all small enrollment courses aren’t contributing to the university’s bottom line.